Every few months, we see the same headline: “Hydrogen cars lose the race to EVs.” But beneath the soundbites, are we comparing apples to oranges?

This post will also ruffle some feathers so disclaimer: FLOAT supports any activity to reduce CO2 emissions. A whole range of technologies are required to meet net zero and we all need to work together to ensure the optimal implementation!

Let’s get one thing out of the way: hydrogen vehicles offer real advantages. Fast refuelling (just a few minutes) and long range (over 700 km) make them ideal for fleets, logistics, and anyone who doesn’t want to plan their life around charging. But today, people hesitate—refuelling stations are rare, and hydrogen is expensive.

Fair enough. But the why behind those limitations—and the standards hydrogen is held to—rarely gets a fair hearing.

Infrastructure: You Can’t Use What Doesn’t Exist

Yes, hydrogen refuelling stations are scarce. But that’s changing.

In the UK and Europe, we’re seeing a shift toward hub-based refuelling, where demand is localised—think logistics yards and bus depots. Projects like Tees Valley Hydrogen Hub and HyHaul are leading the way. These hubs can support back-to-base operations and with enough of them it begins to seed a network, much like how EV infrastructure started.

Cost: Yes, It’s High—But That’s Temporary

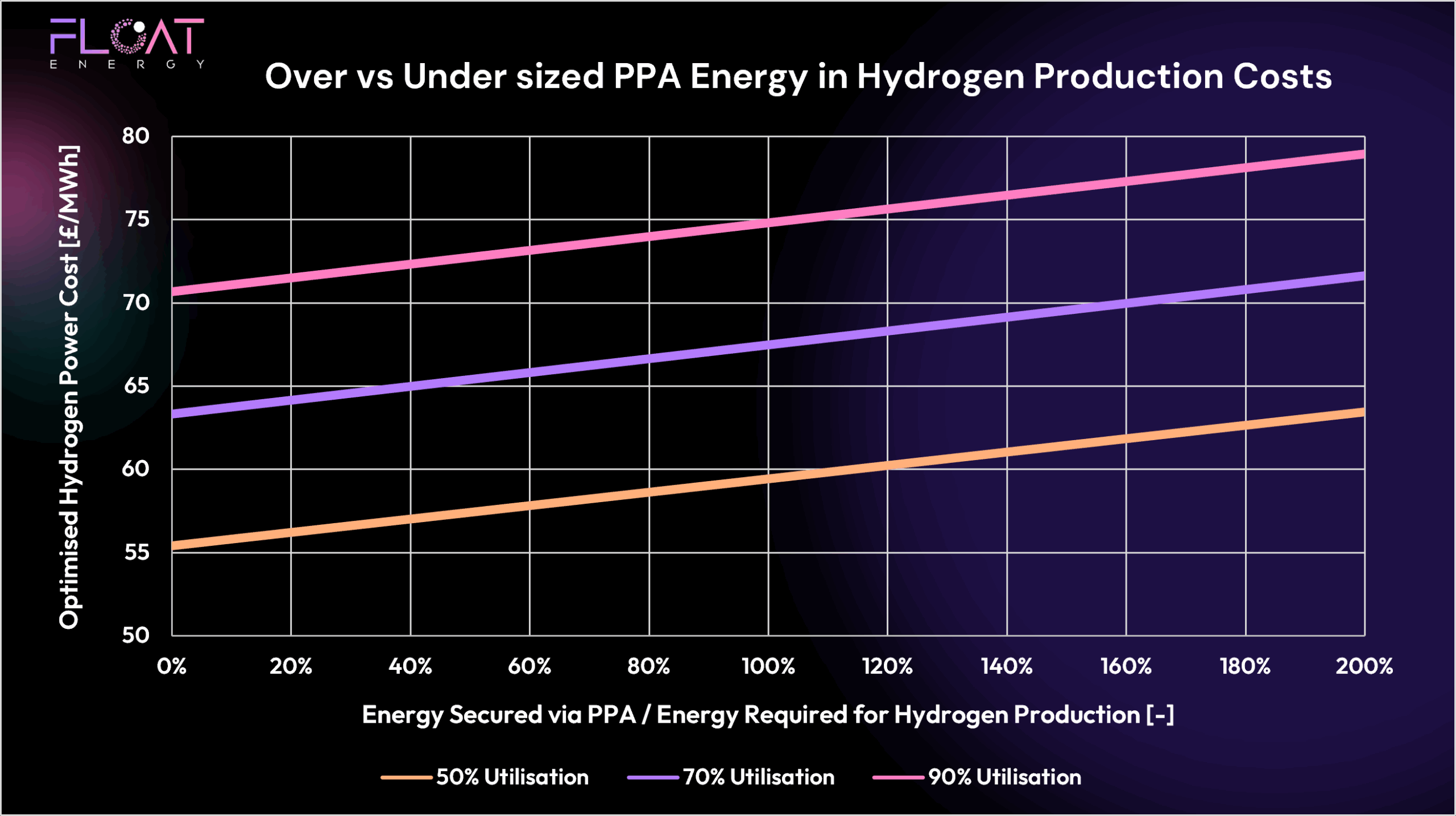

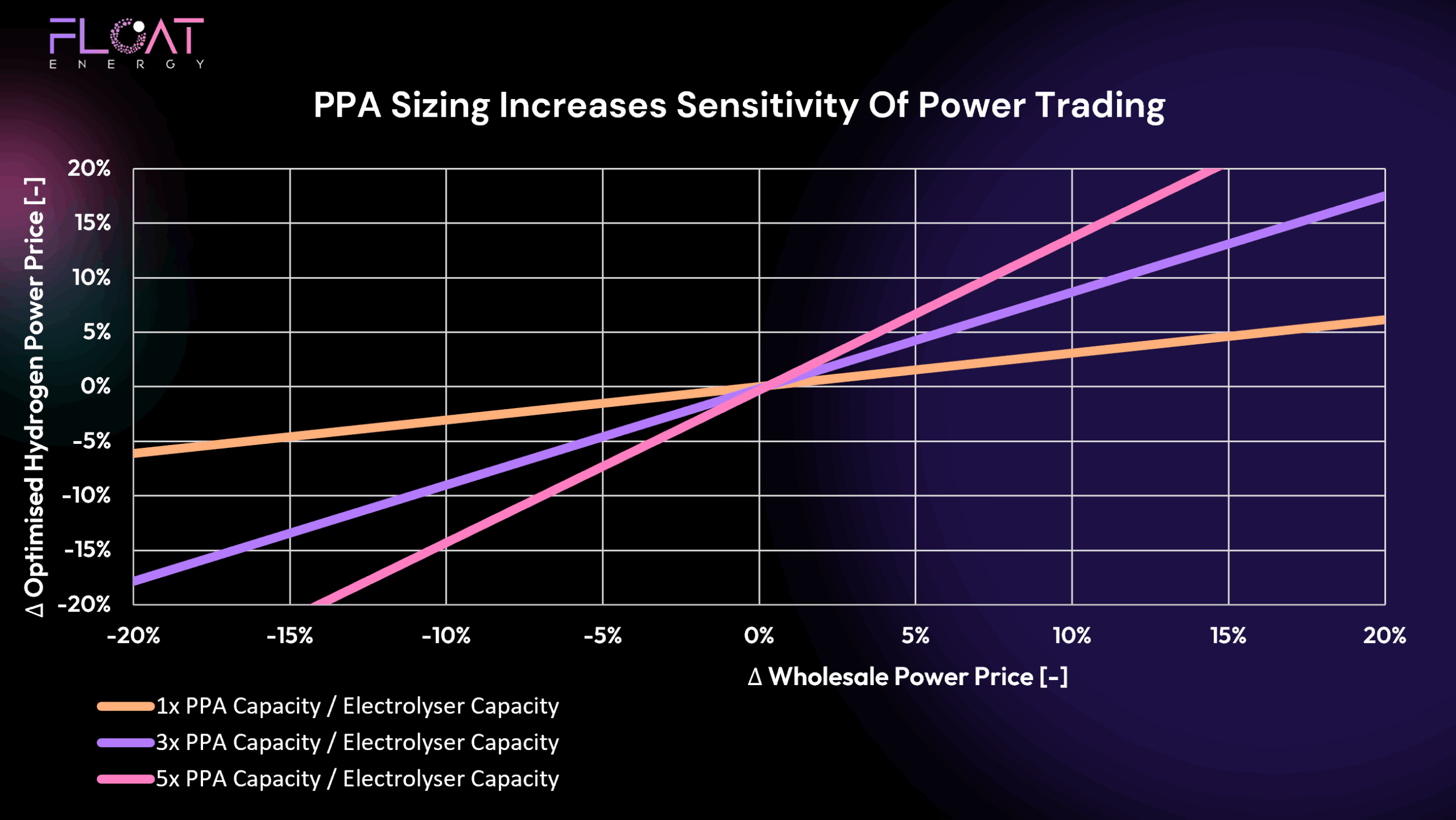

Hydrogen today is expensive. But low-carbon hydrogen production is scaling. With UK HBM contracts and EU-backed projects coming online, we’re going to see cost reductions—just like solar and wind before it.

The key is committed offtake. To get hydrogen at low, stable prices, users need to sign long-term contracts—something very few EV owners have to think about when plugging in at home and another (potentially unnecessary) hurdle for hydrogen users.

Now for the Unfair Bit

It’s popular to claim EVs are “greener.” But how green is the power charging your vehicle overnight? It’s definitely not coming from solar panels.

Most EVs charge overnight. While wind contributes, the UK’s marginal power source—especially overnight—is often natural gas. So unless you’re explicitly charging when the grid is clean, your EV may be emitting more CO₂ than you think. A lot of the carbon lifecycle assessment we see for EV’s are predicated on using near zero carbon electricity sources.

Furthermore, if you’re charging in the daytime at normal electricity rates then perhaps hydrogen won’t start to look so expensive!

Meanwhile, hydrogen in the UK must prove its carbon intensity every 30 minutes to meet government standards. No offsets. No annual averages. No “REGO-backed” creative accounting. Just real, measured carbon data.

Why the double standard?

We’re not saying hydrogen is perfect today. But we are saying it’s held to a higher standard. And if EVs were held to the same rules, we might have a more nuanced debate.

Innovation Gets Left Behind

Hydrogen internal combustion engines (ICEs) could offer cheaper, rugged alternatives to fuel cells—especially if they can tolerate lower purity hydrogen. But in the UK, hydrogen ICEs aren’t considered zero-emission. That regulatory position risks stifling innovation before it even begins.

A Call for Balance

EVs have a huge role to play in decarbonisation. But so does hydrogen. Comparing them without acknowledging differences in infrastructure maturity, regulatory hurdles, and carbon rules does hydrogen a disservice.

As we saw with HVO and biofuels, the real carbon story often emerges years after the hype. Let’s not make the same mistake again.

Want to Dig Deeper?

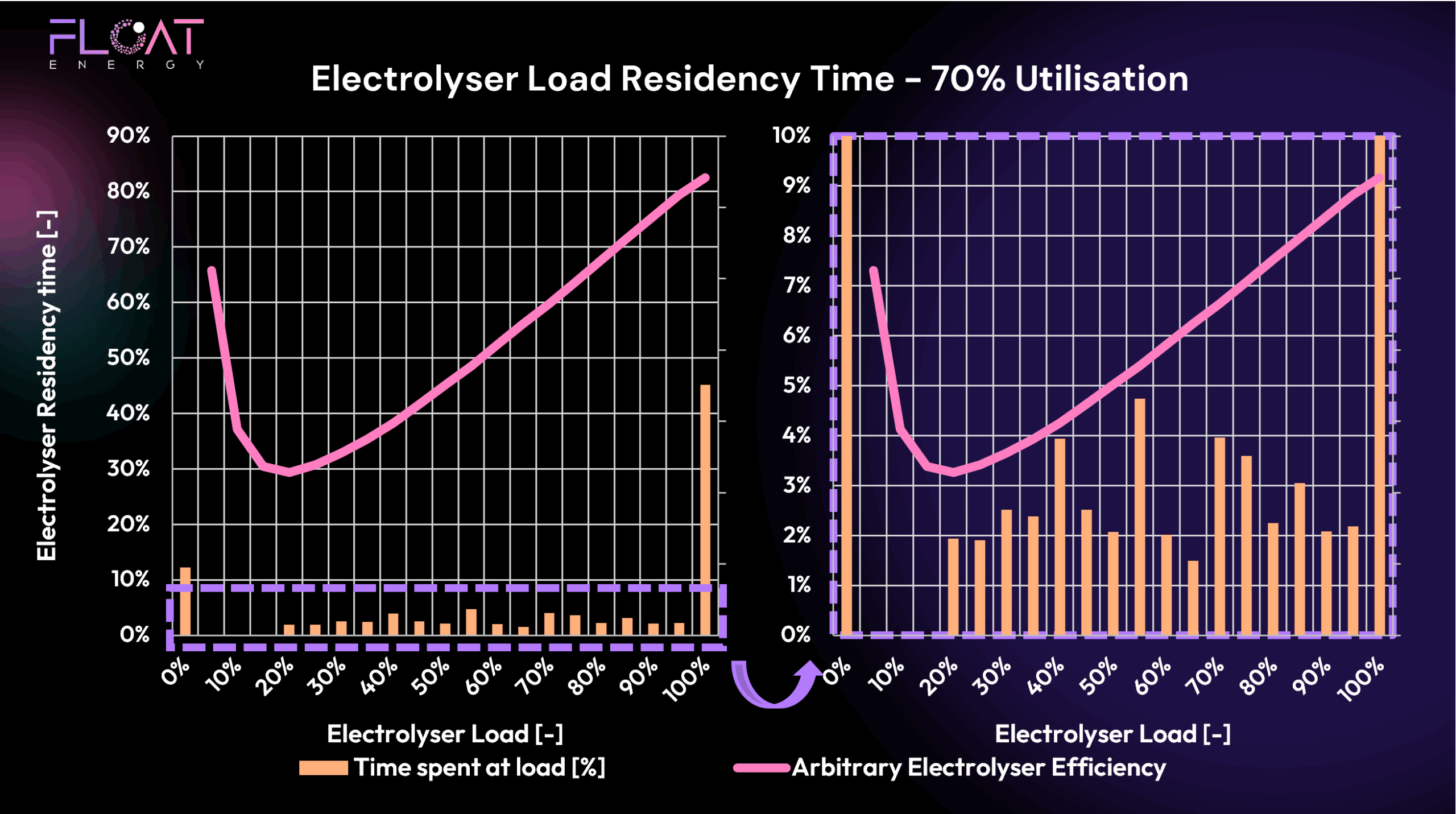

At FLOAT, we’re helping hydrogen producers optimise cost, CO₂, and certainty —from the optimising design during planning to providing optimisation revenue during operations. If you’re trying to navigate the evolving hydrogen economy, we’d love to chat.